Councilor’s camp concerns spur action; Service providers speak out

One councilor’s off-the-cuff remarks regarding the city’s homeless camp have sparked a community-wide debate. Citizens and service providers are speaking out and making sure people’s needs are met.

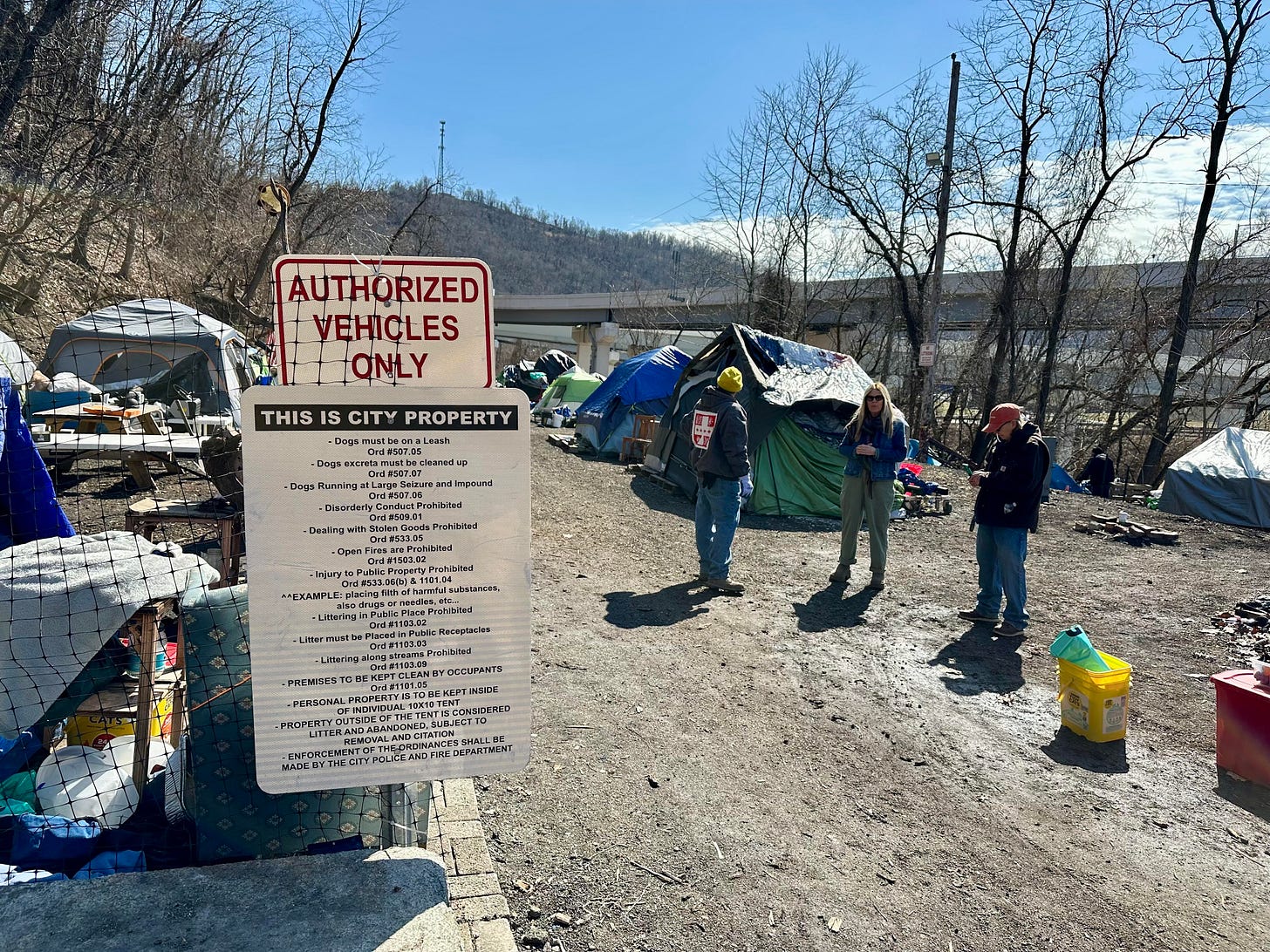

WHEELING – It was a brisk, sunny afternoon in early March when a small group of ten congregated at the city of Wheeling’s exempted homeless camp for a volunteer-led cleanup effort. Dressed in work boots and equipped with gloves, grabbers and trash bags, the group was quick to speak with residents of the camp to understand what could stay and what could go.

The camp stretches roughly 150 feet from end-to-end and sits below Interstate 70’s Exit 1B. Up to 30 individuals live at the camp, but that number is expected to grow when the Life Hub–a low-barrier winter freeze shelter–closes March 31.

The volunteers met that day after a city councilor said he was “disgruntled” by the conditions–and blamed those conditions on local service providers. His assertions were vehemently disagreed with by the organizations that serve the camp’s residents, amid financial and organizational limitations.

Councilor Ben Seidler used his time at a Tuesday, March 4 city council meeting to take aim at Wheeling service providers he said aren’t doing enough to maintain the camp.

Seidler said the intent behind the camp was for service providers to offer resources to the city’s homeless population at a central location.

“That’s not what’s happening,” Seidler said before telling groups to “step up and get it together” or he would call for the camp’s closure.

Josh DeShong, a resident of the city’s Center Wheeling neighborhood, turned the councilor’s comments into action. He reached out to a community group chat to organize a cleanup at the camp.

“I mean, it seemed like an easy fix,” DeShong said. “If the complaint is ‘Oh, there’s garbage,’ it seems like it’s kind of easy to go pick it up.”

The volunteer-led cleanup was DeShong’s first time at the exempted homeless camp. He said the area was much smaller than he expected.

“The way they talk about it like some sprawling thing–it’s not that at all,” DeShong said. “You can see it from start to finish.”

Asked about the level of trash in the camp, DeShong said it was not as bad as Seidler and other city leaders have made it out to be.

“They made it out like it’s a dump. It’s not any worse than any other part of Wheeling, you know what I mean?” said DeShong, adding that he’s constantly picking up garbage from the front of his own home.

Local nonprofit Street MOMs also played a key role in the clean-up organized by DeShong. Operated by Susan Brossman and Lynn Kettler, the organization provides the camp with tents, blankets, sleeping bags, cold-weather gear, clothes and other essentials. They pushed back on Seidler’s assertions that city service providers are failing to properly manage the camp.

“We are two 60-some-year-old volunteers that come out every week,” Brossman said. “We do our part. It’s very hard to hear that, instead of somebody from council thanking us for what we’re doing, they say we’re not doing enough.”

Street MOMs has also long struggled with access to the camp. The entrance to the site is locked, with only city employees, police and fire departments having keys to open it. Last summer, Street MOMs told Wheeling Free Press they were locked out for roughly an hour with no one to let them in.

“We’re here every week,” Kettler said. “We’re here two, three times a week, but we have never really officially been given access to the camp.”

Funding is another issue. Although Kettler and Brossman estimate that some 60 percent of the camp’s residents have struggled with opioid use, no money from the state or city’s opioid settlement funds has been spent directly on the camp’s residents.

Since disbursement began in May 2024, the vast majority of city and state settlement funds have gone to the Wheeling’s police and fire departments: approximately $618,000 and $422,000, respectively. $150,000 was awarded to an eight-member collaborative to help households pay for utility bills and avoid eviction, while $5,500 went to WTRF-7 News for a special on the opioid crisis.

Kettler said she hopes some opioid settlement funds will be used to open additional sober living homes.

“You cannot go to rehab, come back out, come back to this camp and stay clean. I couldn’t do it,” Kettler said.

In response to Kettler’s comments, Brossman mentioned a man she’d just spoken with who was in recovery and living at the camp with his father after being evicted.

“He was clean. He was trying to stay clean. He had been clean for quite some time. He left Huntington to come back here to his family,” Brossman said. “I just asked him, ‘So, are you able to stay clean?’ He said, ‘I ain’t back on the needle, but I’m trying my best.’ “He’d be perfect for sober living.”

Another organization regularly serving the camp is Project HOPE, a collaboration of medical professionals and social workers who provide medical care and follow-up appointments for homeless people throughout Wheeling.

“We go anytime we get a call–one to three times a week,” said Dr. William Mercer, who leads the organization.

He added that other organizations, like Street MOMs, Catholic Charities Neighborhood Center, the Greater Wheeling Soup Kitchen and the West Virginia Coalition to End Homelessness are often at the camp too.

Asked about the agreement Seidler claimed service providers were not upholding, Mercer said he didn’t know of any such official arrangement.

“I know there was ongoing discussions with pretty much everybody involved,” Mercer said. “But then we were hit with a kind of snafu when we weren’t able to get many of our requests answered. So everybody just kind of disbanded.”

Despite the setbacks, Mercer said a managed camp–a system where city employees, service providers or another third-party monitor a site, enforce rules and provide essential services–could work in Wheeling, but not without funding.

“But it comes down to the question of who would fund this,” Mercer asked. “I don’t feel it’s fair for the city to expect [service providers] to do it without any reimbursement. Everybody has their budgets.”

Responding to Seidler’s claim that service providers needed to “step it up,” Mercer said they already have.

“You talk about ‘step up.’ I think they’ve gone up so many steps. We call it ‘the stairway to heaven,’” Mercer said. “But we need to be more focused. And, again, I don’t think anybody expects everybody to do this for free.”

While there is no silver bullet to solving homelessness, organizations throughout the city of Wheeling are doing their part to help those on the streets. Their biggest ask is financial and organizational support, not opposition, from the city’s leaders.

Councilor Seidler did not respond to a request for comment for more information about his comments or to respond to the statements made by citizens and service providers.

I work in the field of mental health and substance abuse disorders and have first-hand knowledge about the cycle of addiction. I believe in the medical model of addiction.

That being said, I believe that I am a qualified professional to make the following statement.

To address the issue of dispersement of funds, I will start by telling you that I have not yet seen any such resources from the opioid settlements dispersed equitably to each person who suffers from Opioid Use Disorder or OUD.

Granted, the many agencies involved in this epidemic need financial resources to do the most good for the community: police, EMS, fire departments, medical providers, and the list goes on.

However what I have NOT seen is the dispersement of funds to

individuals who live in the camps.

From my time walking the camps to provide services, I did not observe one single individual who directly benefited from the funding. Has any individual received a housing allowance? No. Has any individual been provided with any funding to reinstate a driver's license or to be able to pay fines? No. What about funding for a treatment program? No. No. No. And no.

How can we expect people to get clean/sober if they do not have the resources to treat a mental health disorder or SUD?

Generally, when a person is in survival mode, he/she has to focus on the very basics just to sustain life. A person isn't focused on the future when he or she is dealing with hunger, lack of shelter and making it till tomorrow.

If we really want to address the opioid epidemic, we must address the basic individual needs first.

Another way that funding could be used to benefit the individual and the community is by offering education to the public and those who are afflicted with this disease.

There is not just one magical answer but rather a combination of treating the whole person with an individualized treatment plan.

And finally, addiction is a physiological process that consumes a person, and they no longer have the ability to "just stop" or to use willpower alone.

I would like to propose having a community education event where the members of the community are able to attend an evening event to learn about the cunning, baffling and powerful disease of addition.

What people don't understand if you are homeless you don't have to be a drug addict and anyone can be homeless if city council people too