Future of Paden City High School remains unclear following hearing

Judge Wilson extended his injunction on the closure of PCHS through August 1; however, new bombshell data could spell disaster for the school's future.

NEW MARTINSVILLE, W.Va. – A sea of green and white washed over the Wetzel County Courthouse on Thursday, July 25, as hundreds of Paden City residents gathered for a court case that will decide the fate of their town’s beloved high school.

Although no final decision was made, a lifeline was granted through an extension of the injunction while Judge C. Richard Wilson weighs the evidence, including a bombshell claim by the defense that dangerous levels of benzene exist in the school.

This isn’t the first time the community has come out to defend its school.

In 2010, the Wetzel County Board of Education considered merging Paden City High School with another county school. That ultimately failed, but in 2023, a similar vote was considered. Both times, hundreds of residents came out to protest and, both times, the votes failed unanimously.

On June 12, Wetzel County Schools Superintendent Cassandra ‘Cassie’ Porter invoked W.Va. Code §18-4-10(5) to close the school due to PCHS’s location atop a U.S. Environmental Protection Agency designated Superfund site. After Porter’s decision, the residents of Paden City again protested their anger this time outside of their high school.

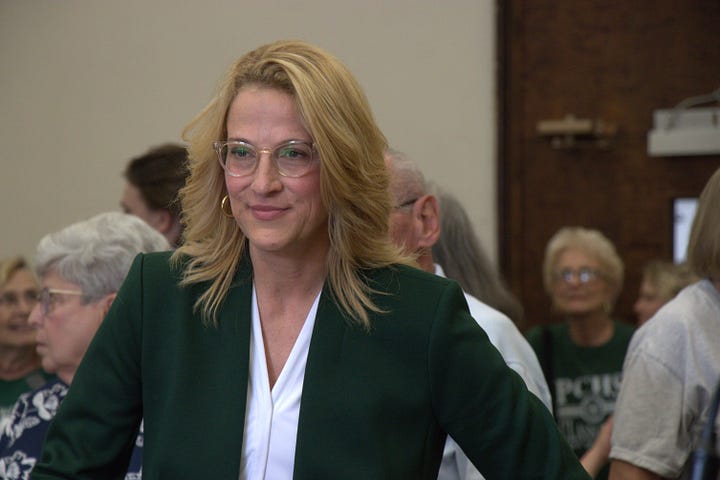

Just one month later, a lawsuit was filed by Wheeling attorney and state attorney general candidate Terisa Toriseva on behalf of over two dozen parents, coaches, and teachers, seeking an injunction to the closure. Judge Wilson granted as much, allowing for athletics and band practices to resume, and set a preliminary hearing for July 25.

Over one hundred people, braving the heat of the day, waited outside the courthouse for a chance to see the proceedings. Parents, grandparents, and PCHS students of past, present and future, took a moment to pray for their Lord to be present in the courtroom. By 4:00, the time when the hearing was set to begin, a county sheriff called out that all the seats had been filled.

One mother desperately pleading with the sheriff to let the school’s students in. He stood resolute, offering his sympathies, but reaffirming the courtroom’s capacity.

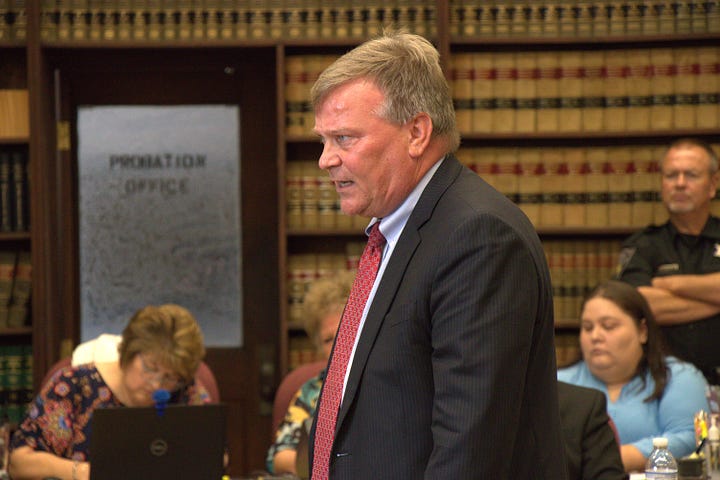

Inside, roughly two hundred people sat shoulder to shoulder on the pew-style benches of the courtroom. Proceedings began just after 4:05. To Judge Wilson’s left sat the defendants, Ms. Porter and her Charleston attorneys William Lorenson and Kenneth Webb, as well as counsel for the W.Va. Secondary Schools Activities Commission Steve Gandy. In front and to his right sat attorneys for the plaintiffs Toriseva and Joshua Miller.

The crux of plaintiff’s arguments regarded the lack of imminent harm to students. It was true that PCHS sat atop an EPA Superfund site–a designation made in 2022 due to a large plume of toxic Tetrachloroethylene (PCE) in the groundwater likely caused by an historic dry cleaner’s company nearby the school. Plaintiff’s argued if the school was safe for the 2022-23, and 2023-24 school years why was it now not?

Further, when the school was ordered closed by Porter on June 12, an EPA spokesperson quickly responded on June 13 saying the agency did not recommend closure. Instead, the EPA said they informed Porter in May that there was “no unacceptable risk” to students.”

The EPA routinely monitors “vapor intrusion” of PCE into the school. White results show negligible levels of PCE in the school, the EPA has said changes in weather or the foundation could increase exposure.

Plaintiff’s called their first witness, Aaron Billiter, chief water operator for Paden City and PCHS coach, who testified to his involvement in discovering the PCE contamination in 2013. Billiter, on cross examination, asked if PCHS was unsafe due to a city-wide issue shouldn’t they shut the entire town down? After testifying, Billiter abruptly left the courtroom.

When plaintiff’s called Porter to testify temperatures quickly rose. Attorney Miller, reading the code Porter cited to close the school, confronted her in saying there was no imminent risk to student’s health. Defiantly, Porter spoke of a February 2024 EPA test in which she said “there are problems.”

Porter refused to say when she received those results or what they showed until her attorney’s, the defense, began their cross examination at which point she immediately recalled that she had received the tests on June 24–two weeks after she closed the school.

When asked why Porter did not release the test results when she got them, she claimed it was because they are public knowledge. This reporter has not been able to find that data. Rather, the only mention of benzene on the Paden City Superfund site is from a January 2024 report stating “[benzene] was not detected in samples above health-based screening values.”

Those test results allegedly show benzene levels from .36ppm to 1.1ppm throughout the school. For reference, OSHA sets limits for workers at 1.0ppm during an eight hour workday. During cross examination of the defense’s expert witness Phillip Simon, plaintiff’s were able to establish that benzene can be easily and relatively cheaply removed from the school using an activated carbon filter.

Benzene is a known carcinogen that is most often found in areas where historic gasoline was stored. It is not related in any way to the high school’s location atop a Superfund site despite that being the reason for Porter’s closing of the school.

Judge Wilson, noting that this hearing broke the record for attendance and length–6.5 hours in total–said he had much to consider. He instructed the parties to draft their orders with facts, findings, and conclusions, and extended his injunction to Thursday, August 1 at midnight. Wilson thanked those in attendance and, in true West Virginia fashion, warned folks to be aware of deer on their drives home.

The fate of Paden City High School is still unclear. On one hand, it appears Porter’s decision to close the school on June 12 was without merit–the EPA, whose Superfund designation she cited for its closure, did not show imminent harm nor did it recommend closure. However, if the benzene results prove true the judge could be sympathetic to keeping the school closed.

If the school does close, though, it will be devastating for the community.

Paden City Councilor and PCHS teacher William Bell cited research that shows a 40% decline in property values after a school closes in a town. Bell went on to state it could be traumatizing to a community where a large percentage of kids already come from trauma.

Dalton Hays, a sixteen year old student of PCHS and member of the band, said he did not feel welcome at Magnolia High School. Hays’ father testified that closing the school and moving students to MHS would be like taking a child from a loving home and forcing them into foster care.

Billiter, who was the first to testify, said his two children, a rising junior and senior respectively, would choose homeschooling over going to Magnolia High School. He said his home was a “somber place” after the closure announcement and spoke of his daughter, Laiken, who he says has lost forty pounds since the closure was announced.

Porter, for her part, testified that Paden City High School lacked adequate staffing prior to the 2023 school year questioning whether students are receiving a quality education. The school would also struggle to maintain its state-mandated insurance through the Board of Risk and Insurance Management (BRIM) due to that policy’s exclusion of protection against pollutant or chemical exposure.

Either way, history will be made in Wetzel County by August 1—a history that will likely be painful for either side of this lawsuit.

The ruling just came down. The school will remain open as if the closure never happened.

Great article! Thanks for covering this. As you can see, this story is about much more than a dry cleaners.

As for the benzene, how serious is that? It sounds like it is over the limit by the smallest amount possible and is easily mitigated. Also, since benzene has nothing to do with PCE, it would be interesting to see the other county schools get tested to see if anything is going on with them. Do we have any evidence the Magnolia's air is cleaner than Paden City's?

At this point, I think PCHS would be one of the safest schools in the state due to how closely everything is monitored.