A West Virginia Story: Industrial Disaster, Environmental Poisoning

One Appalachian's experience with industry and it's shaping of his story. A review of the 2008 Institute, WV explosion, 2014 Elk river chemical spill, Clearview, WV, slurry pond.

The West Virginia story is shaped largely around our industry. While many are aware of our coal industry, what often doesn’t get mentioned is our massive footprint in chemical manufacturing, petrochemical production and the natural gas fracking, and their waste and environmental impact. As an adult I have worked sporadically with environmental activists protesting proposed petrochemical plants, injection wells, and hazardous waste storage sites in the upper Ohio valley. This work is not political for me, it’s personal. My fear of industrial disaster has largely been shaped by my surroundings, yet not many talk openly about the trauma incurred in growing up near these sites; and the training we went through to expect disaster.

I have had the pleasure of speaking with college volunteer groups from around the nation who visit Wheeling. This is when I first started processing these decades of trauma. Growing up in St Albans I experienced several major disasters related to the chemical manufacturing in the area. When I moved to Wheeling I was quickly singled out as someone who could share these personal experiences to highlight the ways in which industry impacts the state. The groups are then taken to a slurry pond (or slurry lake) in Clearview, West Virginia. When I first saw that slurry pond in 2020 it was life-changing. The black, tarry “liquid” held back by towering, radioactive walls of fly ash. The contrast of industrial waste surrounded by our sacred Appalachian hills. It was an experience that once brought me to tears, but now brings me to write.

I want to start by explaining what growing up in St Albans with chemical plants across the river, both up and downstream. This area –part of the Kanawha river valley– is colloquially known as the chemical valley, a nickname you’ll understand by the end of this piece. At night the river reflects as many lights as stars visible in the sky, and the flames of the flares visible for miles. These concrete and metal complexes –these chemical plants– line the river through Nitro, Institute, South Charleston, and Charleston. These plants –some owned by Union Carbide, Dow Chemical, US Methanol, Bayer CropScience, etc– stretch further east to the New River, and further west to the Ohio river. Their complex pipes, spherical buildings, and many smoke stacks are impossible not to notice when driving through these towns.

Life in St Albans was molded by the chemical plants. A siren would sound on the last Wednesday of every month in the city to signal a drill for a shelter-in-place. These sirens are loud, wailing noises that repeat on loop for several minutes. The idea was, in the event of a chemical spill or related disaster, residents would seek shelter indoors immediately upon hearing the sound. Once inside, residents were to tape the seams of their windows and doors closed, put wet towels under the door, shut off your HVAC system, and shelter-in-place until given an all clear.

In elementary and middle school our teachers would semi-regularly go over these steps, on occasion putting a towel under the door and showing us where the duct tape is. By high school the siren’s song was barely noticed, let alone the instructions repeated. If anyone did ask what it was the immediate response was “it’s the last Wednesday.” We were being trained every month on how to respond to hearing that sound on any day other than the last Wednesday. And well trained we were.

This experience was so normal to me that I assumed it was the same everywhere. I didn’t realize it wasn’t normal everywhere when the same siren sounded in Morgantown when I was in college. Upon hearing this loud siren in the middle of the night I, admittedly inebriated, panicked and implored my friends to seek shelter with me. Apparently in some rural areas the fire departments, often volunteers, use these same sirens to signify the need for a response. The sirens sound in Bridgeport, Ohio, across the river from Wheeling, and I think about this memory when I hear them. Now, even later in life, this story about the shelter-in-place drills often elicits sympathetic responses.

My first memory of a non-drill shelter-in-place siren is sometime likely before 2004 when I was no more than seven years old. The youngest of four my nights were often spent at Crawford Field watching a sibling play either football, softball, or baseball. On a warm night I remember my parents rushing me and my siblings back to the car, instructing me to cover my mouth with my shirt. I remember us going home to tape our windows and stuff towels under the door.

When I was in the seventh grade a Bayer CropScience facility violently exploded across the river from St Albans in Institute, West Virginia. At the time my dad was recovering from a surgery. In the middle of the night the house shook violently and I rushed down stairs thinking my dad had fallen. Finding him safe in his chair, albeit as confused as the rest of the family, we went outside where we met our neighbors also standing on their porches. Word was that a fireball flew over the valley, shaking the homes. When I arrived at class the next day we were informed about the explosion and that one person had died– the father of one of our classmates. We were not told much other than the explosion happened. Were we to need it there were counselors available to us.

Let us spend some time on the facts of this case. As mentioned, I had not learned the cause or severity at the time. In preparing this article, though, I did find a 180-page investigation by the Consumer Safety and Hazard Investigation Board available on BayerCrop Science’s website and the CSB’s website.

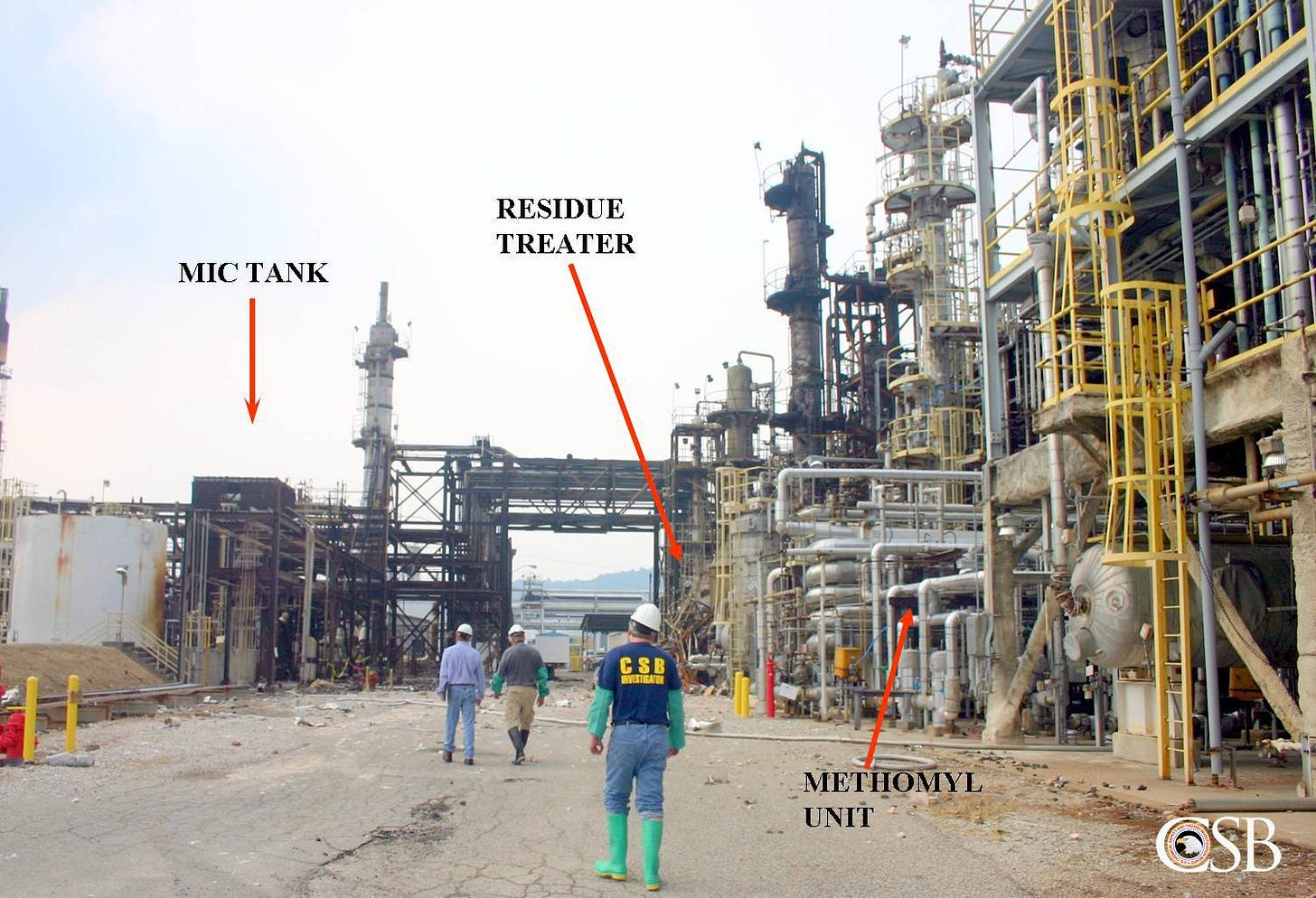

On August 28, 2008, a tremendous explosion occurred in Institute, West Virginia, at the Bayer CropScience pesticide lab. A runaway chemical reaction occurred in a residue treater –a 4,500 gallon pressurized chamber– when methomyl-containing solvent was pumped into the vessel before clean solvent had been added, causing the pressure to rise rapidly and ultimately rupturing. The explosion killed one person immediately, and a second person died later due to his injuries. Eight people were injured.

This part of the Bayer CropScience plant synthesizes the pesticide known as Larvin through many complex chemical reactions involving highly toxic chemicals. The lab had on site storage vessels containing methyl isocyanate (MIC) which Bayer used to produce a dry chemical known as methomyl. Methyl isocyanate (MIC) is infamous for killing more than 3,000 and poisoning more than 540,000 in Bhopal, India, in 1984.

The 2008 Bayer CropScience explosion in Institute, West Virginia, occurred just 70 feet away from their methyl isocyanate (MIC) storage chambers. While the company states no (MIC) was released, the CSB found that monitoring equipment was not operational. Bayer CropScience emergency response teams and site managers did not properly coordinate with local fire departments and municipalities. The Putnam-Kanawha County Emergency Management director, after trying for an hour to reach someone from the plant, unilaterally declared a shelter-in-place emergency for 40,000 residents.

The St Albans fire chief was also unable to get response from Bayer CropScience during the disaster concerning the smoke billowing towards the city, and the potential hazardous chemicals it carried. Bayer, over an hour after the explosion occurred, ensured communities that there was no danger posed by the smoke. However, the CSB report found that the only air-quality monitor on site near the explosion was not operational. To this day the report does not know exactly what chemicals or solvents were released, or what chemicals were produced as a result of the rapid burn-off after the explosion.

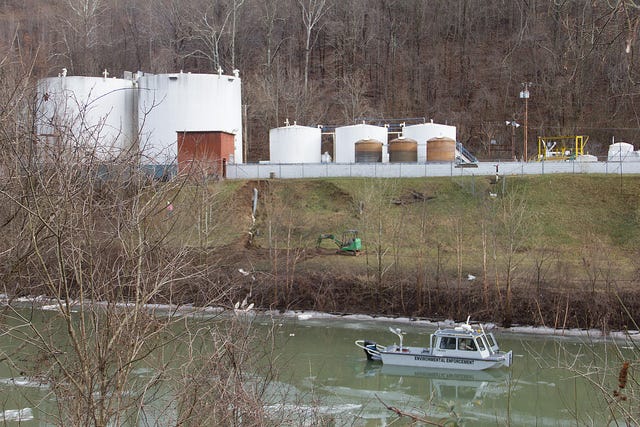

On January 9, 2014, 4-Methylcyclohexanemathanol (MCHM), a toxic chemical used to remove impurities from coal, and polyglycol ethers (PPH) leaked from a Freedom Industries storage facility into the Elk river, poisoning the water for some 300,000 people in West Virginia. The spill was identified by residents of Charleston who smelled licorice in the air, and by Freedom Industries employees around 10 AM. The WV Department of Environmental Protection was on site by 11 AM, noticing few containment and cleanup measures being utilized. West Virginia American Water, which provides water for much of the Charleston region, was made aware of the spill by the WV DEP by 12 PM, but continued pumpling the contaminated water and sending it to customers. By 4 PM American Water employees noticed chemicals flowing past the filtration system but took nearly two more hours to announce to their customers the water was unsafe to use at 5:45 PM.

My family, living just outside of St Albans city limits, was one of many affected. My oldest sister used the tap water to feed her newborn baby. Each of my family members used that water to drink, to eat, to bathe that day. We were poisoned from 10 AM to nearly 6 PM while Freedom Industries, the WV Department of Environmental Protection, and West Virginia American Water knew and did nothing. My parents traveled as far as Kentucky to secure enough bottled water for our family. To this day my parents do not drink the tap water. I remember this affecting my family for at least a few weeks, and by the end we were told to flush our systems, i.e. running our taps to rid the pipes of the chemical. American Water later charged their customers hundreds of dollars for this flushing. Ultimately a class action lawsuit was filed and area residents received meager checks of a couple hundred dollars.

When I moved to Morgantown, as I mentioned, I learned those shelter-in-place sirens weren’t normal everywhere. I also learned different parts of the state have normals of their own when it comes to industry concerns. Morgantown is surrounded by coal and natural gas power plants, including one in downtown. Fracking and coal mining were much more prevalent than my hometown, too. I saw for the first time in my surroundings the parade of huge dump trucks carrying coal through the city, wrecking the streets and causing concern for residents. When I lived in the ninth ward I often was woken up by the industrial park on the other side of the Monongahela river, where they researched new ways to frack.

In Wheeling is where all of these experiences coalesced into action. The hills of the Northern Panhandle hold so many frack pads it's impossible to count. Every bend in a country road seems to have its metal sign with a company name chained to a fenced area. People’s homes sit illuminated all night, counting half a dozen fracking sites on adjacent hilltops. Once I went to the rural hills outside of West Liberty to watch a meteor shower when, on finding what we thought was a quiet, dark place, turned out to be an orchestra of trucks backing up and the banging of equipment accompanied by a light show turning the horizon an eerie, bright blue. There is no escaping these pads in these hills.

There is a place between Wheeling and West Liberty called Clearview, West Virginia tucked into the rolling hills of the Northern Panhandle. Folks living in Warwood, a neighborhood of Wheeling at the bottom of Clearview, used to dream of buying a home in Clearview. Retiring to those hills was a sign saying “I made it!” Having spent four years in the city I have heard many natives share fond memories of driving through the town. One woman who moved here from Arizona said those hills were postcard-worthy for how beautiful they were.

If you visit this community today, as the students I mentioned previously get a chance to do, you’re not greeted by those postcard-worthy hills, but a truly enormous site of towering pyramid-like walls holding back a still, sludgy, blackwater ocean. You see massive tracks of exposed earth forming roads and paths, evidently an expansion of the slurry pond. You see frack pads dotting the hills around the slurry. The two-lane, narrow country roads are flanked every ten minutes by convoys of five or more brine trucks passing by once quiet neighborhoods. The air is thick with haze, and the smell of burning rubber. The streams leading from Clearview glow a vibrant orange and drain into the Ohio river, upstream of Wheeling.

These ponds hold the waste water, known as blackwater, after the coal cleaning process happens. This mixture of toxic chemicals (like the MCMH which poisoned the Elk river in 2014), coal dust, solvents, and water sits in unlined pits fortified with dam-like walls made from fly ash, another byproduct of coal mining and which is considered radioactive. (Fun fact, the City of Wheeling uses this same fly ash to de-ice roads in the winter). The blackwater sludge is so viscous it cannot be sent to normal purification plants, so it sits in these ponds so the solids can settle and the water evaporates. Inevitably, leaching from the slurry impacts local groundwater. Ultimately, this area, and similar places across the nation with slurry ponds, are now forever scarred by this practice. An untold number of people are affected. And some communities are destroyed when the ponds collapse, as they have in 1972 Logan County, WV, 2000 Martin County, KY, and 2008 Tennessee.

I now see this as a pattern of generational poisoning and robbery. Our state’s history is defined by its industry, and that industry is always at the whim of their owners. For the sake of profits and for the sake of expediency, the State of West Virginia has encouraged corporations to come to this state to steal its resources, pillage its land, poison its people, and pollute its environment, all while taking the biggest paycheck. These resources leave our state as soon as they’re produced, and the profits are privy to outlanders only. The poorest state in the nation is one of its richest in mineral and material. Generations of our men have died for the sake of someone else’s pocketbook, and generations of our men, women, and children have been poisoned from the land, air, and water. Even in the 21st century corporations continue their rampage unabated, including in 2008 Institute disaster and 2014 Elk river chemical spill. The people of this great state are sick and tired, literally. Too sick to fight back and too tired after 250 years of continual poverty. The greatest thieves and robbers of our time sit in our statehouse, in mansions on our hills, and in board rooms counting millions made in our state.

Why share all this? First, I want to have a personal record of the chemical and industrial disasters I’ve survived. Especially in the wake of the East Palestine train derailment, I find it important for people from our region to be clear to the outlanders whose eyes and ears are on us: this is not new. These disasters are commonplace, and we are literally trained to expect them. This is a long read, but they’re all just my personal experiences with disaster as a 25-year-old man. We will better effect change when we listen to voices whose reality is environmental devastation.

Second, I want to encourage other West Virginians to share their stories about the industry in their area. We do not hear in our media the family farm forced to close when a slurry pond buys out their mineral rights. We do not hear the stories of communities whose crick is polluted by derailed coal trucks. We do not hear the stories of people who live next door to Bayer CropScience in Institute, West Virginia, who regularly have to worry about what they’re breathing in. We should tell and hear these stories more as it will help build solidarity between our regions.

Third, and finally, the goal is to be clear in my understanding of why this is going on. I have provided that in a very opinionated paragraph above. To reiterate, this is one of the greatest mass poisonings in U.S. history, yet we do not talk about it. I do not use these words lightly when I say West Virginia is a resource extraction colony. 250 years, generation after generation, of chemical spills, explosions, derailments, while the profits flow out of state and into fat-cat wallets. Enough is enough. None of this is born from politics or theater, it’s born from lived experience and decades of fear. Until we hold our government accountable for allowing businesses to treat our state and our people this way we will continue to decline in every metric. The only path forward is redistribution of our wealth, restoration of our environment, and rehabilitation of our people. Period.